Understanding Clinical Trials

From a scientist’s idea to a manufactured drug, there are many steps in developing and getting approval for medications. In the search for a treatment to combat COVID-19, researchers all over the world are trying to expedite clinical trial processes. But how do we note the progress of a clinical trial and what do they entail? In this post, we break down the different phases of a drug clinical trial into their methods and goals to take you from laboratories to consumer shelves.

Before the trials…. Preclinical Research and Studies

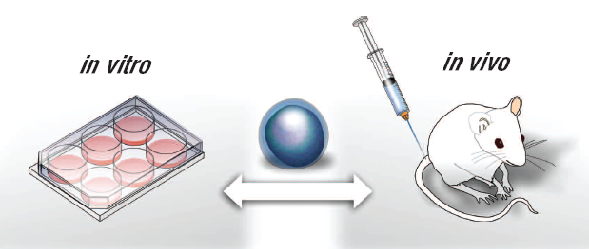

Preclinical research or preclinical studies are done in a laboratory and use in vitro cells or in vivo animal models for testing new treatment candidates. In vitro refers to experiments conducted on lab-grown cells or tissues while in vivo refers to the experiments conducted in living organisms. Most often, laboratory mice are used for in vivo studies.

There are several goals in preclinical research. Scientists can test if their drug candidate is toxic to the lab-grown human cells, get a rough estimate on the dosage that these cells can handle, observe how the drug candidate works at a cellular level, and ultimately, whether these initial experiments provide enough robust evidence to move onto a clinical trial. Once this is complete, the scientists will follow their government’s guidelines in applying to begin clinical trials.

Phase 0

Not always used, phase 0 clinical trials are sometimes considered the bridge between preclinical research and phase 1 trials.

Duration: Varies, but usually less than one month

Participants: Phase 0 trials are conducted on a very small group of people, usually fewer than 15

Method: Participants are given a single microdose of the drug and are monitored to see how the body will react

Goal: The main goal is to observe how the body responds to, and processes the drug. Because the dose given is so low, phase 0 trials are not used to test the safety of dosage or if the drug will work. These trials can be used to determine which drugs show promise in terms of how the body processes them.

Phase I

Moving into phase I, this is the first time the drug is tested in humans.

Duration: Several months

Participants: Usually a minimum of 20 and a maximum of 100 people. Participants must be healthy with no underlying medical conditions. It is only in very specific emergency cases when sick patients are allowed to partake in phase I trials.

Method: Different participants are given varying doses of the drug and then observed to see which dosage leads to the best outcome with minimal side effects.

Goal: The goal of phase I trials is to determine the correct dosage, possible side-effects, safety of the treatment, and formulation of the drug.

As drugs move through the clinical trial process, only a certain percentage make it onto the next phase. ~70% of drugs move into phase II, ~33% of those move into phase III and only ~25-30% of those move on to approval or phase IV (Data Source: FDA).

Phase II

Duration: From several months up to 2 years

Participants: Phase II trials move into a much larger group of participants, often in the hundreds, and this time, it will include patients who have the medical condition the drug is targeting.

Phase II can be split into 2 different stages: Phase IIa and IIb.

Method: Participants are given the dosage found to be safe in phase I, and the drug’s efficacy and side effects are observed.

Note: Efficacy refers to if the drug will produce the desired result (ie: cure or prevent the disease).

Goal: The goal of this phase is to determine how effective the drug is in combating the disease.

Phase III

Once the drug has proven to have a positive effect in phase II trials, they will move onto phase III trials. Phase III trials will compare the new drug with a current ‘standard-of-care’ treatment.

Duration: Usually between 1 to 4 years

Participants: This trial will include up to thousands of participants (with most citations recording up to 3000 participants) with the medical condition the drug is targeting.

Method: The drug will be compared to an existing drug in terms of how much more or less effective it is, what side effects it may cause, and its overall safety. These trials are randomized* and usually blinded* to ensure there is no bias in the results. (*See end section ‘What makes a good clinical trial?’ for more info).

Goal: The goal of this trial is to determine if the drug has clinical value compared to what is already available.

Phase III trials are much longer in duration than phase II trials, so rare or long-term side effects can also surface during these trials. Positive phase III results are usually necessary before organizations like the FDA make public approval on the drug. In certain emergency cases, organizations may expedite this process such as with the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization which allowed immediate use of certain drug treatments. Once approved, the drug can be manufactured and distributed as an approved, usable drug.

Phase IV

Phase IV clinical trials are not always required, but certain companies or authorities may require them to be carried out to monitor any long-term effects (positive or negative) on larger populations for a longer period of time. They can be completed to check safety during clinical use, how the drug works when mixed with other medications, or even by competing companies who are in the market to develop a new drug.

What makes a good clinical trial?

Randomized controlled trial (RCT)

It is a trial where the participants are randomly assigned to different groups: a control group or a treatment group. The control group is either given a placebo, a current standard treatment, or no treatment while the treatment group is given the treatment being tested. There can be multiple treatment groups depending on what is being compared.

Randomization ensures that any kind of bias is minimal due to the fact that each participant has an equal chance of being selected into the control or treatment group.

Blinded trials

Blinded trials can be called single-blind or double-blind trials. In a single-blinded trial, the participants do not know which group they are in: control or treatment. This means that whatever effect the participant experiences will not be biased by their own perception.

In a double-blinded trial, not only are the participants unaware of their groups, but the researchers are also unaware of which group the participants are in. This is thought to result in the most objective results since both the researcher and participant can only report their observations without any perceived or biased observations.

These are often combined into double-blind randomized controlled trials to minimize bias. They can be used in phase II clinical trials and are required for phase III clinical trials.

Journal Sources:

https://academic.oup.com/biostatistics/article/20/2/273/4817524

Media Sources:

https://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/clinical_trials/phases.aspxhttps://www.nhs.uk/conditions/clinical-trials/

https://healthtalk.org/clinical-trials/blinded-trials

https://www.healthline.com/health/clinical-trial-phases#phase-iii

https://www.fda.gov/patients/drug-development-process/step-3-clinical-research

Image Sources:

https://stemcells.nih.gov/info/Regenerative_Medicine/2006Chapter2.htm

https://www.thestreet.com/investing/gilead-successful-trial-coronavirus-drug

https://www.poverty-action.org/about/randomized-control-trials

https://www.liberaldictionary.com/double-blind/